As you can see, there are five columns, and beneath their headings the various candidates for inclusion as "diseases of language" are listed and described. The five column headings across the top read respectively:

"Name of Disease or Syndrome"

"Language/Knowledge/Reality (LKR) Relationship"

"Symptoms"

"Age of Onset," and finally

"Makes Condition Better"

All but the second of these are standard headings in such differential diagnosis tables, to be found in most advanced medical books. That second heading, described as "the relationship between language, knowledge, and reality" (or "LKR"), is explained in great detail in a chapter of my book in progress entitled Where Does Language Stop and Knowledge Begin? It is not at all a difficult concept and concerns the integration of these three factors inside the mind—language, knowledge, and reality—of each individual who may suffer from various imbalances in their functioning that influence each condition being described.

As I mentioned, I have so far tentatively described some twenty conditions that may spring from various imbalances between these three planes. The four conditions I would like to call your attention to here are Graphiphobia, Rhetoriphobia, Dysepia, and Dysglossia. Of these four, the names of the last two at least follow the model of two other recognized pathologies in our field, Dyslexia and Dysgraphia, commonly treated by language therapists.

Let me describe each of these four conditions. For Dysepia, the inability to handle simple questions, the symptoms are "embarrassment when asked to give directions or avoiding the issue, problems in providing simple answers, even when one knows them perfectly well." As for Dysglossia, or the fear of appearing foolish while speaking a foreign language, its symptoms are "false starts in foreign languages utterances, laughter, embarrassment, reverting to native tongue." For Graphiphobia, or fear of writing, its sufferers complain about the "certainty that one will be unable to write about a subject, often a self-confirming fear." Finally we have the extremely common condition Rhetoriphobia, or fear of speaking in public, where we find among other symptoms "inability to begin speaking, freezing in mid-speech, avoiding invitations to speak in public."

Concerning the age of onset, all four can occur at any time of life, though Rhetoriphobia is more likely among younger people, and Dysglossia becomes more difficult to treat during later years. Each of these conditions requires a fairly individualized treatment program, including classes, sessions with others who share the problem, tapes or language labs, and for Dysepia special exercises in giving directions.

But despite these treatment possibilities, countless millions of Americans continue to suffer from one or more of these conditions and go through their entire lives without any significant improvement. If this is not a definition of pathology, then I don't know what else to call it. And if this does not provide clear proof that language is most definitely not an innate gift bestowed on all human beings, then it is possible that those who believe in such nonsense simply don't want to hear any evidence to the contrary.

The other diseases of language I have so far identified and attempted to describe range across a wide spectrum of behaviors, including some conditions familiar to all of us, such as "Tip of the Tongue phenomenon" or what I call Cyclorrhea, or talking in circles, or Logicorrhea, a form of conduct not totally unknown among linguists, an absolute fixation on logic, as defined by the speaker. But such breakdowns between Language, Knowledge, and Reality can also encompass far more severe and socially prevalent imbalances such as literal-mindedness, or related disorders springing from an obsession with rules, or perhaps even so widespread a condition as social or personal hypocrisy. I am still working to perfect these categories and believe that I will soon be able to describe them in greater detail.

I hope I have begun to give you a rough idea of the material that will be contained in the differential diagnosis sections of my work in progress, once I have finally found a publisher for it. There are just one or two other aspects of medical linguistics that I'd like to mention briefly. In one piece I made widely available on the web and on USENET newsgroups five years ago, I remarked that one of the chief shortcomings of the MIT-LSA school was their total inability to conceive of the sheer physicality of language.

One would-be critic of my position so completely misunderstood this statement that he assumed that mentioning physicality could refer to one thing and one thing only: gestures as language, which was already well covered by linguists. But of course I did not mean that at all, I meant that even though our most eminent pundits imagine language to exist almost entirely on a sublimely mental and intellectual level, the point I was making was that almost everything about language can just as readily be described as largely physical to one extent or another.

Those who do not understand this will have a great deal of difficulty if they ever try as adults to achieve near-native capability in a foreign language. This is because the mechanisms for saying the sounds and words and sentences of a foreign language correctly are essentially the same as the mechanisms for learning to catch a ball. The only difference is that the muscles involved are far more minute and the degree of swift coordination required is far more sophisticated. Much the same skills are at play in appearing "witty" even in a single language—one may think of a witty remark but still not be able to utter it at precisely the right moment. In this way physical agility also plays a role in perceived mental alertness.

If you will permit me just a touch of levity at this point, I would like to suggest that perhaps the most frightening of these diseases of language is in fact one suffered by many working linguists, namely Morpheme Addiction. But as serious as this can become, we would do well to remember that it can lead to an even more alarming condition: Premature Sememe Emission.

My purpose in including this section today has been to give you a rough idea of where my thoughts are headed in developing a physiology of language. I think I have now succeeded in doing that, and I'd now like to move on to the next topic.

6. Some Further Details about my Gedanken-experiment

(Though this section is presented in full below, to save time during the workshop it was summarized in a few brief paragraphs. What follows here is a shortened version of Gross, 2003, available in its full form on this website by clicking here.)

Now I'd like to say something more about that Gedanken-experiment I mentioned on Wednesday, which fully backs up my contention that there is nothing wrong with translation that is not also wrong with language itself. In other words, when the Harvard philosopher W.V.O Quine discussed what he called the "indeterminacy of translation," what he was really referring to was the "indeterminacy of language." In this description I am borrowing from the version published in one of that seemingly endless series of volumes by John Benjamins. (Note 1)

Our experiment begins with the assumption that a group of highly trained journalists has gathered in a room and is seated around a table. These journalists, all roughly of the same age, are seasoned and respected members of their profession. Moreover, they have all studied at the same school of journalism and received their training under the very same professors. It might therefore be assumed that they not only spring from a common background but that they also share overall outlooks and attitudes towards writing and editing to an uncommon extent.

These journalists are now presented with a paragraph written in their native language, along with blank sheets of paper, and are prompted to compose a paraphrase of this passage. Since paraphrasing is a common journalistic exercise and bears a close resemblance to work they routinely perform each day, namely editing, they all immediately set to work, and each one creates his or her own paraphrase of the very same text.

It would be theoretically possible to assume, given the nearly identical background of the participants, that their paraphrases would turn out to be remarkably similar, differing only in a few slight touches. But I do not believe for an instant that this would prove to be the case, nor do I anticipate that any reader sophisticated about the nature of language will draw such a conclusion. If, in fact, we now collect these paraphrases—five or ten or however many there may be—and read each of them aloud to our circle of journalists, I believe we will be amazed by how many different approaches have suddenly sprung from the same original passage. And if this is our result among this remarkably homogeneous group of journalists, it will surely take place to an even greater extent among writers or journalists coming from more diverse backgrounds. And if we now choose to substitute translation students for journalists and ask them to translate rather than to paraphrase a brief passage, I do not believe that any reader will doubt that something remarkably similar will now take place, on this occasion involving two languages rather than a single one.

I also fearlessly predict that the various individual differences of style and wording we discover, whether among the journalists or the translators, will fall into two general categories. The first of these, by far the greatest number, will consist of slight liberties each of the journalists has taken with the original text in creating his or her paraphrase. In fact, as the various versions are read aloud, our participants may even begin to disagree with each other whether or not a specific word or phrase is an adequate equivalent for the word or phrase in the original.

It is likely that most of their discussion will be devoted to such minor disagreement, most often friendly and collegial in tone. The task of creating an ideal text—as neutral in tone as possible while still perfectly representing the original—is one that journalists face each day. It is for this reason that reporters at major publications may, where necessary, rewrite, reedit, and/or "re-tweak" each other's work, always in the hope of approaching ultimate perfection, much as the lonely translator—or the translation editor—must do in creating a final draft.

But there is also almost certain to be a second category of divergence present in the journalists' work, one which will provoke somewhat more heated discussion. It may well be discovered that in at least a few instances one or another of these professional writers has committed an outright error of paraphrase, has in fact actually overlooked the meaning of a word or phrase in the original text and replaced it with what can only be described as an incorrect solution.

At this point the purpose of the experiment will have certainly become clear to readers. What we have just discovered while using a single language is so remarkably close to what can happen while translating between a pair of languages as to be for all practical purposes indistinguishable. We all know perfectly well that a group of professional translators sitting around the same table and presented with a paragraph to translate into a second language would surely go through a remarkably similar process. And once their translations were collected and read aloud, these writers would certainly also embark on a similar series of discussions and disagreements.

In other words, the idiosyncrasies of trained writers are indistinguishable from those of trained translators, and vice versa. Whereas society at large tends to accept such variations by journalists, that same society tends to focus on them if translators have been the perpetrators, even to suppose that something in the process has gone seriously astray. Indeed, this plethora of individual variations has not escaped the attention of machine translation specialists, who have in some cases chosen to view them as evidence that human translation is unreliable and must one day be replaced by the trustworthy logic of computer programming.

At this point, a closer look at this experiment can be helpful in providing a few practical examples of what might take place. And since machine translation has been mentioned, it may also be useful to glance at the problems programmers might face in an attempt to improve on the work of human translators. The following sentence, taken at random from a historical text, will play the role of our paragraph to be paraphrased:

In April, 1900, the position of Peking had under these rapidly developed circumstances become so dangerous for foreigners that it was deemed advisable to dispatch a relieving force from the port city of Tientsin.

Now let's see what a paraphrase of this sentence might look like if we change as many of the original words as we possibly can:

By the early spring of 1900, because of these swiftly unfolding occurrences, the situation in the Chinese capital had grown so perilous for outsiders that it was considered prudent to send assisting troops from the coastal town of Tientsin.

We can see immediately that the paraphrase has become longer than the original passage (a common outcome in many translations from English as well), but other differences are also obvious. While the paraphrase conveys the essential meaning of the original, a number of questionable changes have been made, though perhaps only one could be characterized as an outright error. This comes at the very beginning, for by changing "In April, 1900" to "By the early spring of 1900," a certain degree of precision has clearly been lost. Other possible solutions might be "During the fourth month of 1900" or "As April of 1900 began" or "March was barely over when...," but all of these are overly elaborate and/or add something not present in the original. The original text does not claim that this situation arose "early in April" or "during" April, merely "in April."

On the other hand, the wording of the source text does not provide us with sufficient information about the exact time to proclaim any of these variants as being devastatingly wrong. Perhaps a useful rule of thumb in a manual for paraphrasing would be never to change the names of months or days, though there might be instances, as with all rules of thumb, where this too might work less than perfectly.

A similar problem crops up at the very end of the sentence when "the port of Tientsin" is rendered as "the coastal town of Tientsin." Unlike the month of April, there is no way we can avoid using the name of the town . Even though it would be technically accurate to call it "Tientsin, the port city of Peking," this involves inserting a geography lesson into the paraphrase where none occurs in the original. In any case, a "coastal town" is not necessarily a "port city," nor would calling it "the seaside town" or "the embarkation point" help us very much. "Harbor town" might be even less correct, as a harbor town is not necessarily a port—the word "harbor" describes mere topography (ships may occasionally enter a harbor, but no docking system may be present)—while the word "port" describes a function and often the presence of complex machinery.

Readers are free to examine the many differences between these two sentences at their leisure and are equally free to decide if they can arrive at any truly preferable solutions. These are likely to be few and far between, even though perfectly valid objections can be directed towards every single element of this paraphrase. "To send assisting troops" is not the same thing as "to dispatch a relieving force," nor can "it was considered prudent" be accepted as a perfect equivalent for "it was deemed advisable."

This intricate conversion has taken place entirely in English, a language which we like to believe enjoys an uncommonly rich vocabulary. Yet no end of legitimate questions can be raised about the overall process of paraphrasing, much as they have been raised about the process of translation. In fact, the very level of disagreement likely to arise among readers of this brief passage serves to prove the point being made-that writing and editing in a single language is no more precise or secure than translating between two languages.

Though some of you may disagree, there is probably no major error as such in this paraphrase, as much as it leaves to be desired. Such an error might have occurred if one of the journalists had substituted "Europeans" or "Westerners" for "foreigners," since during this historical episode (the Boxer Rebellion) Americans and Japanese were also among the combatants. Another error might have arisen if the phrase "it was deemed advisable" had been rendered as "it was judged urgent," since this would introduce a true difference in meaning. It may well be that our languages-all languages-provide us with far less "wiggle room" than we are accustomed to believe. While we are capable of saying almost the same thing in many different ways, not all the synonyms in Roget's Thesaurus will unfailingly enable us to convey exactly the same information in all instances—not to mention expressive or emotional meaning. Our synonyms may often not be as fully synonymous as we tend to believe.

Although we have been working within a single language, the similarities with translating between two languages are obvious. Clearly no two "natural" languages have ever been constructed—whether in their vocabulary or their syntax—so as to be fully synonymous with each other, which of course explains many of the problems involved in translation, even before cultural factors enter the picture. None of this of course exonerates the translator from attempting to choose the best possible translation for every word in a text, any more than it excuses journalists from seeking out the very best choice among competing synonyms.

7. Discussion: Can EBL Be Taken Any Further?

(At Dartmouth this discussion took place towards the end of the workshop.)

At this point I still haven't made it to what I regard as my most important section, where I will spell out the nature of the basic structural principle underlying language, which I foresee as taking over the role grammar has played during too much of the past, along with the form of cartographic linguistics that can supplement this new structural principle. And I really do want to get to that.

But I also believe it's time to ask for your participation again, and I want to start things off by asking you first of all about your reactions to my session on Wednesday but then as a continuation also whether you believe the idea of Evidence-Based Linguistics may have sufficient merit that it should be taken forward in some practical way. In other words, do you believe that LACUS, or any other entity, should initiate some sort of effort to take the concept of EBL further and by so doing work to challenge and/or diminish the current prevalence of what I've been calling Voodoo Linguistics. I've already been told by a few of you that it's quite unlikely you would in fact want to take any steps in that direction, since I've also been told that the prevailing mood of the group is that there is really nothing practical we can do about the general climate that surrounds us in our field. In addition, I'll also be offering one or two of my own ideas about what could possibly be done to gently and cautiously alter that climate, but I don't want to get too bogged down in this subject matter during our discussion because I have, well, I've already explained why.

So with the hope that we can keep our discussion down to perhaps 20 minutes, I'd now like to open the floor to any questions or comments about the Wednesday session, or simply how you feel about it in retrospect.

(OPEN DISCUSSION: there was general agreement that the notion of Evidence Based Linguistics should be taken forward in some way.)

And now, provided no one objects, I'm wondering if we can move on to the second theme: is there any practical action or any practical goals any of you feel we should be following to diminish the hold of Voodoo Linguistics both on others in our profession and on the general public, to the extent that the public is aware of these views.

(FURTHER DISCUSSION: It was further agreed in general terms that such practical actions should be taken.)

Okay, let me share with you precisely what my own thoughts are about this subject. One of the aspects that bothers me most is the constant press notice and public reinforcement the doctrines of Voodoo Linguistics keep receiving in the media. Every few months it seems that their spokesmen are busy trumpeting another major step forward in their theories, yet further proof of how triumphant and irresistible their ideas must be. Whether it's the discovery of yet another sign language in yet another country or some reasonably well-known oddity of British speech patterns, there they are, the victorious and omniscient experts insisting that any and all such phenomena provide yet further proof of the resplendent innateness and universality of language in every corner of the world.

I served as head of two Committees for the American Translators Association, first their Public Relations Committee and later the Special Projects Committee, so I believe I may have some insight and experience as to how these continuous press triumphs are being generated. It is no accident that these findings, regardless of their significance, are so well publicized. Just as it is no accident that the leaders of this school are so well versed in George Orwell's theories on the nature of propaganda. Orwell meant these essays as a way of detecting and guarding against assaults on public opinion from whatever source, but when applied in reverse they can also serve as the directions for writing quite effective disinformation.

I believe I can assure you that what I'd like to suggest is something fairly conservative and unlikely to cause any kind of deep scholarly confrontation, though it could serve in the long run to reverse—at least to some extent—current public and scholarly misunderstandings (or perhaps ignorance) concerning those who work in non-mainstream linguistics.

What I'd like to suggest is that someone from this group or another entity get in touch either by phone or email with the principal journalists most likely to write about linguistics and related fields for the New York Times, the Washington Post, Time, Newsweek, and perhaps a few other publications. Perhaps an invitation to a drink or even lunch might be in order. But once one found oneself within personal hearing range of any of these journalists, no hard sell of any sort would truly be needed. One might simply explain to them that there seems to be a great bias in the press favoring one sole school of linguistics. It could simply be suggested that the views of this school are far from being universally shared or even accepted. And a list of the names of dissenting linguists on various topics might even be accepted by these reporters as a welcome gift, since reporting various points of view on any subject is one of most journalists' daily concerns. The names on that list would be likely to include some of the members of this organization. The journalists would then be free to consult them-to consult you-for a dissenting view or not as they saw fit.

Not an earthshakingly radical stance at all, simply assisting journalists to carry out their normal duties. Perhaps you already have someone among you who would be the ideal choice for such a task, or perhaps even more than one such person.

The choice—and how you make that choice—is entirely yours. Assuming you choose to make any choice at all. It just might be a good idea to start something like this fairly soon—in less than a year and a half the 50th Anniversary of the publication that launched the MIT-LSA movement will be upon us, and I confidently predict that we will once again be inundated by all the fulsome exaggerations surrounding this school we have grown so accustomed to hearing. I'd now like to open the floor to discussion concerning whether this might be a desirable step for this organization to embark on. And/or if any of you can suggest some other step that could lead in a similar direction.

DISCUSSION

Mr. Chairman, provided you agree, I would be happy if you would be willing to adjourn the discussion, and I will then proceed with my discussion of the successor to grammar in our field.

8. The Clarification of Context as the Brain's Chief

Language Function: Not Grammar but Linguistic

Cartography and a Unit for Measuring Language

I want to present the cartographical material that follows with a bit less certainty than what has gone before, though I still believe I can present a fair amount of evidence in its favor and that it can prove useful in the future-and perhaps even at present-in helping to advance human understanding and bridging the separations that sometimes arise among both individuals and cultures. It is nothing less than a large-scale attempt to define what language is and how it works. And I will also soon be explaining exactly what the successor to grammar in my opinion is likely to be. I would therefore be grateful if you would all try to put aside previous accounts of our entire field of linguistics, whether based on grammar, or on morphemes, lexemes, and sememes, or on Saussure's Le Signifié and Le Signifiant, and do your best to listen with something like untarnished hearing faculties. I am aware of some imperfections in this account, but I believe that with your aid and comments I may soon be able to correct them.

Some of you may be wondering why I have suggested in my abstract that there can be some connection between linguistics and cartography. But it is precisely this aspect of language which overlaps rather neatly with our conference's other main theme, networks. Almost any map can be converted into a table or data base, just as almost any data base can be subjected to a variety of mapping procedures, and this is of course also true of networks. For me language has always been much more than a mere entity, even more than a process. I have visualized language as an actual place, a territory that contains at least relatively specific locations evolving over time, whose seemingly chaotic and conflicting borders can to some extent be known and mapped. A moving target, to be sure, but one that can nonetheless be predicted, aimed at, and based on one's aim and predictions actually be found.

Can I present any evidence why you ought to believe what I'm about to tell you about cartography? Yes, I think I can. So let me start by confessing that by some unknowable trick of fate, I enjoyed the relatively rare privilege of being brought up among an international family of cartographers, in other words I came to learn the field from the ground up. What follows is in many ways the core of my presentation, so I'd like to proceed a bit slowly and begin by explaining a bit about my experiences as one member of a team of mapmakers.

My father had introduced me to maps almost as soon as I could read, when I was given jigsaw puzzle maps of the US and the world to play with. A few years later he was busy teaching me practical values by assigning me writing and indexing jobs for his various guidebooks. He became a bit alarmed when I moved beyond our planet and fixated on astronomy, during the 'Forties viewed as a totally useless study, and even more concerned when I entered college as a lit major. I had no sooner completed my B.A. degree during the early 'Fifties when he decided that the best way to make me face his version of reality was to exile me to Nassau County to map the many new suburban streets suddenly springing up just outside our city.

I spent an entire summer there and walked up and down perhaps as many as a thousand of those streets. My task was to write down the house number of every street at its intersection with every other street. I was also ordered to make drawings of any unusual curves or turnings in those streets and to visit town and village planning offices to obtain public domain charts for housing projects not yet built. On infrequent visits to our offices in the city, I would also confer with our draftsman, whose job it was to engrave these new streets onto a steel plate, and explain to him the precise shape and position of the new streets I had found. I hope some of you are already beginning to sense the similarities between this process and determining the structure and content of a language.

The main goal of this work was to compile what is called a gazetteer guide to that region, a handy index that could be used by salesmen, policemen, and other visitors to find the easiest route to any specific address. Here is just one sample of such a gazetteer guide-I promise you this will become quite relevant to linguistics in a few minutes-in this case one compiled under my father's directions by my half-sister Phyllis as part of the A to Z Atlas of London:

(SLIDE)

Weston Dri. Stan. 1E 25

Weston Grn. Dag. 1E 55

Weston Gro. Brom. 1A 122

Weston Pl. N8 4E 31

Weston Pl. SE12C 78

Weston Rise. WC12F 63

Weston Rd. N222F 31

Weston Rd. W42D 73

Weston Rd. Brom.1F 121

Weston Rd. Dag.1E 55

Weston Rd. Enf.2B 10

Weston St. SE12C 78 (3)

In this table abbreviations such as Brom. and Dag. stand for districts in London, such as Bromley and Dagenham. Here's a piece from another gazetteer guide, this one from a rather outdated world atlas: (SLIDE)

Loachapoka, Ala.G5 113

Loami, Ill.D4 124

Loange (river), AfricaF6 63

Loango, Fr. Eq. AfricaJ12 64

Lobatsi, Bech. Prot.D2 68

Löbau, GermanyF3 37

Lobaye (river), Fr.Eq. AfricaK10 64

Lobdell, La.J1 129

Lobdell, Miss.B3 135

Lobeco, S.C.F6 150

Lobelia, W.V.F4 158

Lobelville, Tenn.F3 152 (4)

As you can see from the names of nations no longer in existence, such guides require frequent revisions.

Here is a third such gazetteer guide, which as I will soon be explaining most closely reflects the structure of language:

Prairie Street

Pine 9

Brewster 21

Cherry 32

Apple 42

Belmont 61

Strawberry 73

Peach 82

Tremont 91

This one shows at what number on Prairie Street the various streets intersecting it will be found. But it does not show in any way how far any one street necessarily is from the one preceding or following it. To discover this you will need to turn to the map itself, and to understand the reason for any seeming anomalies you might need to visit that neighborhood for yourself. If you do, you may well discover that Cherry Street is much closer to Brewster than Brewster is to Pine, or that alternately Apple Street is much further from Cherry than Cherry was from Brewster. This can happen for a number of reasons, including abandoned or burnt out houses, intervening schools or hospitals that take up more space than one family homes, changes in zoning plans, projected structures that were never built, or hills and declivities in the terrain. A major public highway which appears on the map will not appear in the gazetteer guide because it does not intersect the street but passes over it.

In an analogous way, the precise space between possible meanings of words, whether adjectives, nouns, or verbs, may not be marked by the availability of words to fill each shade of meaning. Words can overlap or even conflict with each other, sometimes we have too many to represent a meaning, sometimes too few, and no language can boast a vocabulary that precisely reflects all possible meanings, simply because it is the language itself that determines which meanings are most essential. And no two languages, as you know, do this in precisely the same way.

Here too I hope you will begin to sense a certain family resemblance between networks of place names and of lexical items. We were of course allowed some leeway in our mapping process, simply because no map can ever be perfectly accurate, any more than can any translation between languages or any paraphrase within a single language or for that matter any dictionary. But what we were not allowed is far more important than what we were. We were absolutely not permitted to make up our own street names or shapes or locations, and it would never have occurred to any of us to limit the number of the types of streets that could be mapped or develop ornate or sublime metatheories about what the purpose of a map might be, much less actually transform such theories into mentalistic, formalistic chimeras. Moreover, every step we took in creating our maps came close to observing scientific method: research and/or observing the evidence, conferring with others about this evidence, and integrating it into existing knowledge.

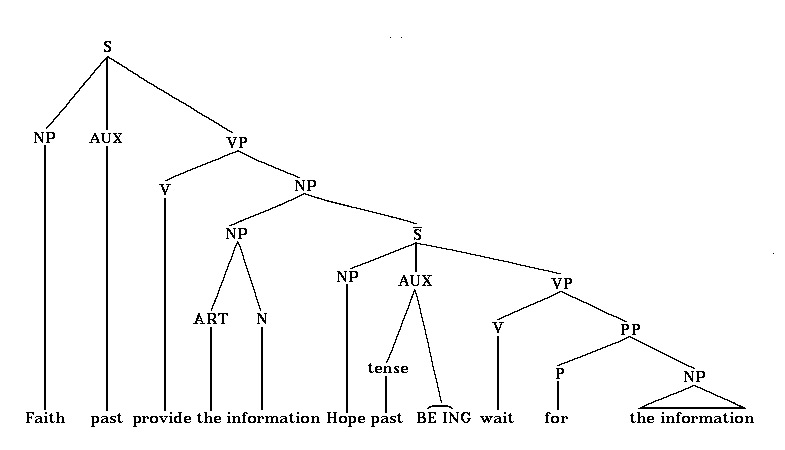

Which brings me to the never-ending use of those famous sacred diagrams invoked by several generations of linguists. Here's one of them (SLIDE):

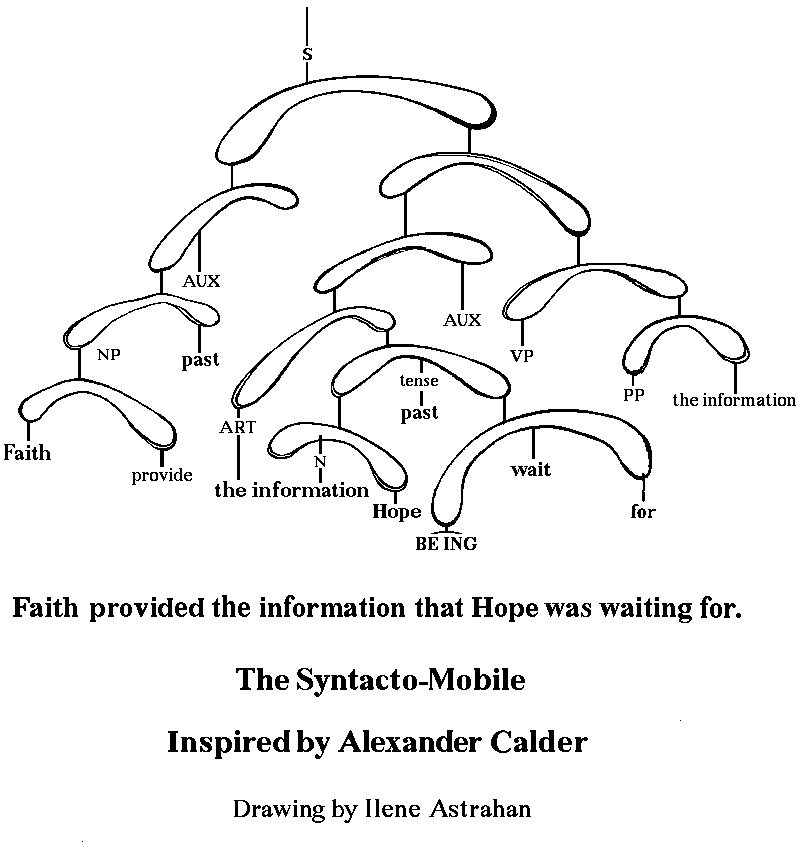

I suppose they have a kind of totemistic, fetishistic value, but when my wife first laid eyes on one, she couldn't stop laughing out loud. "Why, they're nothing but Calder mobiles!" she exclaimed. And here, with a bit of help from Ilene, is what she saw in them, a genuine example of the Syntacto-Mobile: (SLIDE)

These diagrams, since I believe I'll soon be showing you something a bit more revealing, have very little value in elucidating the structure of language. I wouldn't be surprised if they end up in history next to quaint phrenological maps of the human brain or charming illustrations of the language of flowers or theories coordinating each color we see with a musical note. This is because they are essentially based on nothing more than grammar, and grammar is simply not the basic underlying structure of language. As I am about to show you, and of course I will be presenting at least preliminary evidence for this statement. I strongly suggest that the following slide will provide you with a far more useful guide into the basic principles of how both language and a significant part of human cognition are likely to work. And once again I can show you some evidence to back it up.

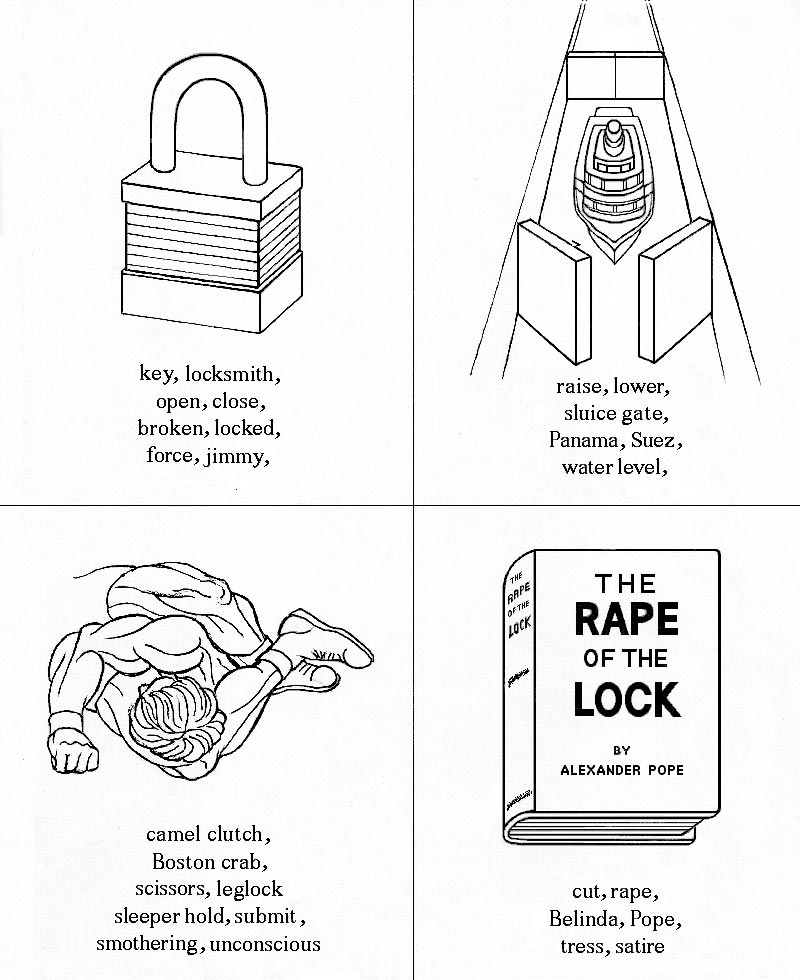

Here, in this page from my work in progress, you see illustrated what I believe the mind does when it hears or sees in print the word "lock," which as you know can have at least four possible meanings. (SLIDE)

Immediately on hearing or seeing this word, our minds look and/or listen to determine what other words we can find being used around it, either in the same sentence or a nearby one.

It's something like the concept of a "proximity search" as used in natural language processing. If the mind hears the words key, locksmith, open, close, broken, locked, unlocked, force, jimmy, door, gate, for example, then it immediately concludes that it is dealing with that kind of lock. It's important to notice that nouns, verbs, and adjectives are all jumbled up together in this assemblage, with no real concern for grammatical roles. The purpose of such a list is to determine that we are dealing with the kind of lock that goes in a door.

While many axons or neuromolecular subroutines may be at work to support this conclusion, this is in fact the nature of the act of cognition that takes place, and I believe that Sydney Lamb has correctly described the abstract process involved in such disambiguation in his own work. In this context, grammar is merely an inefficient add-on with no real consistency between one language and another. The real work being done is in fact described by the first, second, and sixth draft laws of language and linguistics.

If on the other hand the mind hears or sees in print such words as raise, lower, sluice gate, Panama, Suez, water level, shipping, tonnage, or cargo ship, the mind then concludes that we are probably dealing with a lock in a canal.

But what if the mind hears or sees some of the following words: camel clutch, Boston crab, scissors, headlock, hammerlock, leglock, sleeper hold, strangling, smothering, pain, pin, submit, unconscious? Such a mind is likely to conclude that the topic involved is wrestling.

Now let's take a slightly more recherché example and assume that the surrounding words are cut, rape, Belinda, Pope, or tress. Here it turns out that no strange Papal crime is being committed, rather we are dealing with a lock of hair, most probably as part of a discussion of Alexander Pope's famous satiric poem The Rape of the Lock.

Now some of you may object that the last example could only be found in highly informed and literate circles. But the truth of the matter is that the other three examples are equally the product of highly developed and specialized cultural knowledge, only a bit less obviously so. As I said on Wednesday, a great many words—far from representing eternal or universal verities—are in fact culture- and time-dependent artifacts. First of all, locks in canals are a relatively recent development, as are canals themselves, despite the efforts by the Egyptians in 1300 B.C.E. and the Grand Canal built by the Chinese Emperor Yang Guang in 604 C.E. (Note 2)

But there certainly was a time when canals did not yet exist, there are areas of the world where canals are still unknown, and there are doubtless people in our own culture who haven't a clue what a canal lock is. What's more, though various cultures have employed locks on doors, there have been other cultures that have lacked doors to put them in. So this meaning has also not necessarily existed in all cultures at all times, any more than the object itself. We like to assume the word lock is simple, but like many words in all our languages it contains a great deal of what I call "embedded process," encompassing diachronic, social, and cultural development over time and many languages.

I suspect we're all aware that just as light may bend while travelling through space, so human cognition can actually bend and change as it passes through time. And cognition often becomes partially transformed as it passes into other languages. No language other than English uses this same homonym "lock" for all four meanings, which means that the French or German brain will need to sort through quite different choices.

So let's get one thing quite straight. The basic linguistic process is not grammar at all, which can at most be viewed as a supplemental system frequently ignored by those who use language. What's more, I believe I can show you that much the same process is at work even where no homonyms are involved at all. It is in fact this network of systematized disambiguation that runs language.

Disambiguation is a long and clumsy word, so I prefer to call it the clarification of context. If I were speaking French, I suspect I would probably call it le débrouillement de contexte, even though two dictionaries tell me that débrouillement is now rarely used. Even so, the French simply love the verb débrouiller, which means roughly to "defogify," and also the noun or adjective débrouillard, which simply means clever, someone who knows how to defogify, to cut through the fog and the thicket of language and get to the real meaning. And even crosses over into the practical domain, where the French word can mean just knowing how to get things done.

The English also pay tribute to this process when they talk of "muddling through," which means not so much defogifying as getting along despite the fog. And that is what both we and our brains spend most of our time doing, defogifying language and trying to extract the clearest meaning possible. Given the time limits in everyday conversation, it is often a necessarily quick and dirty process, as I have mentioned in the Sixth Law. And often enough we also make mistakes. But it is through these mistakes, if we analyze them, that we can actually peer in at the workings of the brain and grasp what they must be doing, even if that activity on the neurocellular level evades us.

If this were an LSA conference, I'm sure some of my audience might want to fall back into comfortably cushioned thought patterns inside their minds at this point and claim this system is merely warmed over semantics. But it probes much further and far deeper into the nature of language. All semantics has come to mean over time is that we sometimes disagree about the meaning of words. But what I'm talking about here is a tool that can delve far more incisively into both the structure and the development of language, physiologically, synchronically and even diachronically.

I realize of course that some of you here have been wedded for so long to the notion that grammar comprises the true structure of language and have indeed been working for years and even decades to find a way of proving this thesis. I therefore want to offer my sincerest apologies for advancing what may seem to you an altogether unlikely alternative. But as dismaying as you may find such assertions to be, I must confess that I was equally dismayed when I first began my readings in the history of linguistics and discovered that simply because detailed systems of grammar had been devised by the Indians and Greeks and Romans to describe their languages, more modern linguists have accepted quite uncritically such explanations as the only ones worth examining.

Now I'd like to go straight to the crux of my topic and explain what I mean by the unit for measuring language I mentioned in my abstract. Now the moment I mention measuring unit, I can well imagine that at least some of you will be having one or both of two different reactions. How on earth can there be a measuring unit for language, you might well be asking, since both its spoken and written forms are so remarkably irregular? I'm also busy wondering if a few of you may not be harboring some extremely misleading preconceptions about what a measuring unit has to look and sound like. Quite likely, you expect a measuring unit to be precise and unvarying, so precise and unvarying that it can readily be used to measure any quantity at all of whatever it is that is being measured, be it a foot, a quart, a kilo, an astronomical unit, or a light year. After all, what else can a measuring unit be but precise and unvarying?

Actually, as can so often happen, reality is about to intervene and decisively challenge this assumption. One of the most effective measuring units I've encountered, and also one of the best known throughout the world, is in fact the Chinese Inch, or tsun, which can—at least theoretically—be slightly different for every single person on the planet. It is the precise length of the second inside joint on your (or anyone's) middle finger when you join that finger and your thumb in a circle (demonstrating). And since most human bodies are built proportionately, this distance is almost unfailingly precise in making measurement for and on each human being. It is used to measure the position of acupuncture or massage points (or attack points in the martial arts).

I'm assuming it's permissible to introduce a term, a concept, and a tool from Chinese medicine into our scientific discussions. This would not have been the case ten or fifteen years ago, and twenty-five years ago I had an interesting encounter over this issue with a remarkable defender of Western science named James Randi, better known as the stage magician the Amazing Randi. On that occasion it was I who challenged Randi, rather then vice versa, when he made the assertion in a national magazine that all of Chinese medicine was superstitious nonsense. In the end it was Randi who conceded he was mistaken and sent me a gracious apology.

But to get back to the tsun, it is of course quite different for small children than for adults, In other words, it is a truly human measuring unit since it grows as we grow. I believe it is therefore a unit like the tsun that is most effective for measuring language, since language grows as we grow. When we are children, we know comparatively few words well enough to distinguish between them, and we recognize relatively few phrases or collocations or concepts. But as we grow older we gradually become acquainted with a growing number of words, phrases, collocations, and concepts, and what will count as one measuring unit can easily expand in size as we grow more able to organize and mobilize our understanding.

And parenthetically, come to think of it, this seemingly exotic notion is not really so exotic after all—we Westerners do something remarkably similar with kids' shoe sizes or with children's clothing sizes in general. Most important, both the Chinese inch and the standard for language I am about to propose share one outstanding quality: they are commensurate to human beings. Unlike the metric system and even unlike some older non-metric units, they are not an attempt to impose a formalistic, abstract, arbitrary standard onto people, rather they spring out of our very nature as human beings.

So this is essentially the second leap that I am asking you to take with me, to accept that a somewhat variable measuring unit can nonetheless be used to measure somewhat variable areas. It is neither a fuzzy unit nor an imprecise one, any more that kids' shoe sizes are fuzzy or imprecise, it is merely a commensurate unit. If anyone here still finds this leap a bit difficult to take, with all respect I'd like you to consider the following. It's hard enough for most people, myself definitely included, to handle any new combination of words, at least the first time we encounter it. But the leap I'm asking you to take isn't just a new combination of words, I believe it just might qualify as a new conceptualization of how all new combinations of words fit together, perhaps even a part of a new linguistic theory. So it could just be that some of the forces mentioned by Kuhn in his scenario for paradigm shifts might be at work here.

It is not a perfect or precise measuring unit, but then neither are our languages either perfect or precise. Nor are a number of the units used by physicians to measure various physical processes inside out bodies, and frequently enough we find new measuring devices introduced that impose slightly different scales of measurement. But most sciences have developed such measuring units, and it seems to me that it could be quite useful if we linguists could come up with at least some rough form for such a unit as well.

First let me give you an example of such a unit in action. Let's suppose that I've just phoned you up and asked you to meet me in New York at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Thirty-Third Street. "Yes," you reply, "I'll be there, at the corner of Fifth Avenue And Thirty-Fourth Street." I immediately correct you and say "No, not Thirty-Fourth Street, Thirty-Third Street."

The amount of mental energy it requires for me to make this distinction and for you—or any other person—to register that you have grasped it, that precise degree of language comprehension is equal to one of my basic units for measuring language. Essentially, its purpose is to define and measure the smallest and most irreducible element of meaning.

Its size and shape will vary according to the context, not to mention the age of the language user and the level of that user's vocabulary. Let me remind you again that I am not referring to lexemes or sememes or morphemes, which are indecipherable as such units for most people and not much more useful than etymology, but the words and phrases we use in an everyday manner in everyday conversation.

Other such examples would be:

Not chocolate but vanilla.

San Francisco, not Los Angeles.

I said buy, not sell.

The Baltic nations, not the Balkan nations.

If you prefer a definition more in keeping with the terminology of physics, let's call it:

"the cognitive energy needed to move one basic burst of communication from one mind to another (or to other minds equally attuned), assuming close-to-ideal contextual conditions."

This can vary considerably according to the contextual situation, as I will soon make quite clear. Now that I've explained what this unit is, I would like to provide it with a name: (SLIDE)